Content Notes: Mental Health, Neurodiversity, Bipolar Disorder, Plurality/Multiplicity, TERFism, Personal Identity, Posthumanism. Length (~18K). PDF.

0. Vicious Cycles

Another year, another extended absence. What a year though, right? Given how 2020 has demolished any claim 2016 had to the title of ‘worst year in living memory’, and that 2008 and 2012 weren’t exactly peachy, I’m really not looking forward to seeing what 2024 will bring.

For me, last year saw another entry added to the list of ways in which my body is trying to sabotage me, and it wasn’t even COVID-19! I can now add mysterious metabolic problems that translate carbohydrates into crippling fatigue to a list that already includes chronic cervicogenic headaches and poorly managed bipolar disorder. Trying to sift discrete symptoms from the cacophony of miserable noise has been pretty difficult, and it’s taken a long time not just to glean what was going on but to find a dietary regime that leaves me cogent and capable most of the time.

Worse, this all started after a medication (baclofen) that really helped with the above mentioned headaches induced an extended period of hypomania which resulted in a significantly worse depressive crash than usual. (Score one for the hypothesis that mania causes depression.) Add in the nightmare that is caffeine withdrawal, and January-March 2020 was extremely unpleasant, even before the pandemic hit and our collective perception of time coiled in upon itself, turning each day into an exercise in coping with indefinite isolation. In particular, watching myself try and fail to deliver comprehensible lectures on Aristotle to first year undergraduates as, unbeknowst to me, my morning croissant slowly sent me into a stupor, felt like some special Sisyphean punishment for my hubris in thinking I could ever be a university lecturer.

For much of last year I felt like an away message in human form: “I’m afraid Pete isn’t here right now, but he will be sure to get back to you when he is able. Normal service will resume shortly.”

1. Absent Selves

The dysphoria associated with catastrophic dysfunction of those capacities with which one most identifies is hard to describe, let alone define. It’s a curious feeling of absence. As if one isn’t really present, even when one is. Or maybe it’s something like a generalised imposter syndrome, in which one is put in the unusual position of impersonating oneself. Everybody has bad days, bad weeks, and sometimes longer slumps, but they don’t always produce this type of dysphoric interruption in the circuit of self-recognition. This might be because they don’t always come with the fear that the slump won’t end, or that the missing capacities won’t come back. The fear that, contrary to the message you’re repeating to yourself and those around you, normal service will never resume.

Alas, this fear can grow and reinforce itself over time, as episodes come and go. It’s hard to hang on to inductive evidence that the sun will in fact rise again when the darkness comes, especially when each night seems just a little darker, and each dawn just a little dimmer. Anticipation of the new day gradually sours into mourning for the days gone by. This makes it quite easy for other, less cyclical disruptions to trigger the same sorts of anxiety and dysphoria as the more regular ones. And so, the familiar coping mechanisms kick in: One waits. One defers. One apologises for any inconvenience caused by the disruption to normal services. And one promises to get back to everyone once one has gotten back to oneself.

I think that’s probably enough introspection for now. The ostensible purpose of this post is to once more let people know why the blog has been silent, and to promise that, in fact, normal service will be resuming in some form, at least until the next time it isn’t. Last year I’d gotten into the habit of using the blog to collate and comment on some of the things I’d written elsewhere on social media, and though I’ve been characteristically silent for quite some time, I have a stash of half-finished posts from back then that I intend to revise and release at a pace compatible with my other activities. There’s also plenty of new content from Twitter to collate and curate for consumption here.

However, I’m of the belief that, much as we learn more about neurological function by examining cases of neurological dysfunction, we can learn a lot about the nature of self-identity by examining cases in which it breaks down in various ways. It’s much easier to treat the self as a simple, indivisible substrate of experience when one has not seen how the sausage of selfhood is made, and it’s much easier to treat personal autonomy as a given when one has not experienced the ways in which its supporting machinery malfunctions. My hope is that those of us who have some first hand experience of the sometimes dysphoric fact that selves are constructed, might contribute to that most (in)humanist of projects — the task of building better selves.

2. Abject Bodies

Many such contributions already exist, and they take many different forms. But right now, allow me to exact some small revenge upon my body, wretched meatsack that it is. I have grown more and more critical of the discourse of ’embodiment’ over the years, even as it has proliferated across the academic landscape. There are various reasons for this, some of which I’ve outlined in a recent interview with Anthony Morgan for The Philosopher‘s issue on Bodies. However, there’s an aspect of my position that I don’t present there, not least because it’s more controversial: my growing suspicion that enthusiasm for ’embodied’ takes on everything from cognition to political praxis, and the historical narratives that organise them encourage an uncritical valorisation of the body that blends seamlessly into normative naturalism. This is to say that an intellectual tendency which prides itself on the radicalism it displays in breaking with tradition can easily be used to support certain forms of conservatism we should find deeply worrying.

For instance, I think most of us can get behind the idea of enabling people to love their bodies, by working to dismantle beauty standards that not only socially disadvantage those who fail to meet them, but can psychologically harm those who internalise them. But I think we also see that there’s a fine line here between enabling and demanding, especially when the actions in question are aimed at changing systemic features of the wider cultural, political, and economic context. We shouldn’t demand that everyone love their body, especially not those who are disabled by it in some way. If they can love it, and want to love it, we should both allow and support them to do so, but we shouldn’t begrudge anyone their ambivalence, uneasiness, or even their hate. This is my body, there are many like it but this one is mine, and my hate for it is mine to dispose of as I wish.

However, critiques of elective cosmetic surgery can easily slip over this line and into a more or less explicit aesthetic naturalism. In fact, the murky boundary between what counts as elective cosmetic surgery and what counts as expected reconstructive surgery, both philosophically and clinically, demonstrates the extent to which such naturalism already lurks in the background when it comes to the provision and justification of choices made about our bodies. This applies to questions about women’s reproductive choices as much as it does to their cosmetic ones, and clearly extends into questions about treatments and surgeries used by trans people to bring their biology in line with their gender identity. There are plenty of bioconservatives agitating along both of these lines, and there are new and quite troubling alliances across them.

Given that philosophical arguments are already being brought to bear in these ongoing political conflicts, we must be scrupulous in denying bioconservatives the ideological resources of normative naturalism on which they subsist. In my view, bodily autonomy (or better: morphological freedom), is the limit-case of personal autonomy as such. It must be defended staunchly wherever necessary and ratcheted aggressively wherever possible. No doubt some will find my worries here to be spurious, as there seems to be a wide gulf between work on enactive cognition, embodied phenomenology, or new materialist feminism and the pet pedants of the transatlantic TERF set. Well, consider the following question: does the demand to identify with my body entail a corresponding demand to love it?

One might reply that I’m as entitled to hate myself as I’m entitled to hate my body. True enough, but the rational basis of this hate is different in each case. There may be good reasons to hate oneself, and good reasons to hate one’s body, but are good reasons to hate one’s body always good reasons to hate oneself? Of course, there are irrational hates, maybe even delusional hates, and we might in some sense be entitled to them too, but it’s not the type of entitlement that comes from justification. My question is: Can one be justified in hating one’s body without hating one’s self, or can this only be characterised as a delusion induced by the ideology of disembodiment targeted by the radical critiques mentioned above? Is it a symptom of Plato’s insidious influence, perhaps proceeding through Augustine’s denigration of the flesh? Or is it a symptom of Descartes’ disastrous dualism, or the myriad mistaken metaphors for mind it begat in subsequent centuries?

Okay, that’s too many rhetorical questions and way too much alliteration. Let me simplify the question then: How much of one’s body can one rationally hate without the belief that one does not hate oneself becoming delusional? This question is a serious test of the constitutive claims of the embodiment paradigm, because it threatens every foothold established in arguing for the importance of the body to understanding the mind: I don’t hate myself, I hate my tools (extended mind?); I don’t hate myself, I hate my environment (embedded mind?); I don’t hate myself, I hate my peers (situated cognition?); I don’t hate myself, I hate my musculo-skeletal system and the cut-rate motor cortex that steers it (enactivism?); I don’t hate myself, I hate my gut, heart, brainstem, and even my sodding amygdala (affect theory?); I don’t hate myself, I hate my scarred hippocampus (???); I don’t hate myself, I hate my prefrontal cortex and its lousy excuse for executive function (???); I don’t hate myself, I hate the stupid variant of the CACNA1c gene lurking in each and every one of my cells (???); fuck it, I hate my whole fucking brain (materialism?). How far down this hateful path is too far?

3. Abstract Brains

And so we find ourselves knee deep in the mereology of hatred, trying to work out the sense in which hating a part implies hating a whole. This is made particularly difficult by the fact that we’re considering relations of functional composition that aren’t straightforwardly spatial: my immune system is a part of my body qua organism (a subsystem), but it isn’t localised in the way that a limb or an organ is (a continuous region), and my genes are a part of my genome (a systemic feature), but they lack even the residual spatiality of subsystems (their instances, though everywhere, are completely discontinuous). To frame this in different terms, we’re actually grappling with the conditions governing identity over time (in contrast to continuity in space), and the extent to which identity of wholes over time (e.g., remaining the same organism) is determined by identity of parts over time (e.g., retaining the same brain).

The most famous problem in this area is the ship of Theseus paradox: wherein each wooden piece the ship is built from is slowly replaced over time, until none of the original pieces remain, before the original pieces are reassembled separately, leaving us with two distinct candidates for identity with the original ship, one that is processually continuous, and another which is mereologically indistinguishable. There’s a variation on this paradox that gets applied to the problem of mind-brain identity, in which individual neurons are gradually replaced with artificial ones, until we’ve replaced them all. There’s rarely any discussion of putting the original neurons back together afterwards, but the worry about processual continuity remains: Is the resulting artificial brain identical with the original organic one? Or perhaps even: Is the resulting artificial mind identical with the original organic one, even if they’re no longer housed in the same brain? This would be to treat the mind as an abstraction that preserves the functional properties of the brain.

It’s worth appreciating that this variant case implies a corresponding sorites paradox: Exactly how far can the process of replacement go before the mind/brain ceases to be identical with the original, given that it seems as if replacing a single neuron can never make the difference between identity and distinctness? The fact that we take ourselves to persist across strokes, head trauma, and even heavy nights of drinking would suggest that we could easily lose a single neuron without much fuss. However, there’s a small disanalogy between the two cases here. The ship of Theseus is a sorites problem only if you don’t functionally differentiate between the pieces, i.e., if you assume that they’re basically fungible bits of wood that can be treated in the same way. For instance, it’s possible to maintain that replacing a plank of decking will never change the identity of the ship, but that replacing its main mast will.

It’s only by making the problem recursive — allowing subdivision of the mast into component pieces — that it becomes an unavoidable sorites paradox. The reason this isn’t a problem for the neuronal variant is that it has reached a threshold at which further subdivision makes no difference: we see neurons as functionally indistinguishable atoms out of which cognitive systems may be built. In essence, we only have a true a sorites paradox when we’re dealing with a heap of qualitatively homogeneous matter.

This may already be too much mereology for some readers, but it’s really only the beginning. Both these cases only consider changes that preserve functional properties of the system as a whole, but some of the changes that organisms undergo don’t work this way, most obviously growth and decay, which involve functional changes that develop or diminish the system’s capacities. If we want to talk about minds and brains, then we’re also going to have to talk about learning and forgetting amongst other things. Even if the mind is a functional abstraction, it’s one that necessarily accrues significant functional modifications over time: expanding, revising, compressing, and sometimes even shrinking its capacity to recall and process information as it does.

Moreover, there’s no reason we can’t extend this abstraction beyond the brain narrowly defined to incorporate those functional features of the nervous system, respiratory system, digestive system, musculoskeletal system, local environment, social context, and available equipment which the different strands of the embodiment paradigm treat as constitutive features of our cognitive architecture. This means that there’s a cybernetic variant of the ship of Theseus for every supposedly indispensable component of the mind, in which we substitute it for a functionally indistinguishable one, creating concrete cyborgs with the same abstract minds: humans with artificial organs, limbs, lymphocytes, and organelles; people with virtual workspaces, toolkits, colleagues, friends, and maybe even family. Worse, if one accepts that, for the most part, increases in capacity do not effect identity over time (i.e., acquiring a new skill does not a new mind make), then these concrete cyborgs can, in some cases, be genuine upgrades of their organic counterparts. To put it in slightly more technical terms, cybernetic subsystems must be able to simulate their organic counterparts, but not necessarily vice versa.

At the bottom of this cybernetic slippery slope lies the possibility of total simulation, or to frame it in more practical terms: mind uploading. For those who refuse to countenance this possibility (and there are many), the only way out is to resist the idea of functional abstraction on which it rests. This means that they think it’s necessary that they are composed of the same matter across time, or a vague amount of the same matter, at least. There’s a rather entertaining argument along these lines made by one of the early church fathers to the effect that lions cannot digest and incorporate human flesh, because God must be able to find and recombine the bodies of all those poor Christian martyrs come the day of judgment. There might even be some who think this sufficient for identity across time, and so get quite particular about the disposition of their mortal remains, regardless of their functional composition.

However, it’s important to see that the cybernetic substitutions just considered collapse into cybernetic sorites as soon as one suggests that underlying matter makes a contribution to a system’s identity conditions that’s independent of its functional contribution to the system as a whole. And this is where vagueness becomes problematic, because it doesn’t seem like there could be any principled way of delimiting precisely which and/or how much matter is necessary to sustain identity. As such, if one is to avoid sliding down the cybernetic slippery slope, one must bend one’s materialism into a some quite peculiar shapes. As far as I can see, there are really only two principled strategies available to those who insist on the primacy of matter, which I’m going to call the gambit of indivisible substance, and the appeal to heterogeneous matter.

The first option is, as it were, to find a ‘main mast’ on which to pin the mind: identify a core component of the organism that cannot be subject to any material substitution without breaking the continuity of the mind from one moment to the next (e.g., a crucial region of the brain). However, there are two obvious problems with this. On the one hand, if the reasons for singling out this component concern the functional role it plays in the system as a whole, then one invites questions about how it plays this role, which in turn invites questions about why its matter couldn’t be changed without preserving it. There really aren’t any good responses to these questions, beyond the bald faced Searlean tactic of insisting there must be some special property of grey matter we’ve yet to even comprehend the possibility of, let alone actually understand. On the other, the resulting position is weirdly homologous to those theories of mental substance to which materialism is nominally opposed. The only thing that differentiates it from postulating an immortal soul is the admission of mortality. Yet even then it’s a very peculiar sort of mortality that’s more precarious than regular death, insofar as the slightest material change in the substance of your indivisible soul is enough to end you, even if the new soul that results is blissfully ignorant of their birth. It’s as if one discarded Descartes’ theory of thinking substance, but retained his speculations about the role of the pineal gland as the seat of consciousness.

The second option is much more subtle. It consists in maintaining that the very idea of ‘homogeneous matter’ on which the sorites paradox depends is untenable. This is the favoured choice of Deleuzians, who are ever eager to demonstrate that difference surges beneath every seeming sameness. To give them their due, there is some logic to denying the Aristotelean proposition that matter is essentially passive potential waiting to have form actively imposed on it from above, if only because the thermodynamic miracles from which the self-organisation, ramifying mutation, and continuing evolution of life spring seem to bubble up from below. The material strata of complex behaviours that have assembled themselves in the billions of years since the quark-gluon plasma cooled down enough to form familiar configurations of particles seem to suggest patterns of emergent causation in which molar structures more or less robust in relation to random fluctuations in their molecular substrate can nevertheless feed on these fluctuations in a way that leads to substantive novelty. On this basis, the proponent of heterogeneous matter can claim that it’s not just the structure of cybernetic signals that’s important to the identity of a system over time, but the texture of the noise through which they surf.

I’ve seen this argument made several times to deny the possibility of transferring cognition from one material substrate to another. Those making the argument are usually content to insist that the certain existence of behavioural differences between these substrates, no matter how small, are sufficient to produce significant and unpredictable divergences in overall behaviour that undermine any claims to persistence across the transfer based on functional indistinguishability. To frame the argument in more plain language: subtle differences in the way a cyborg body responds to its environment that seem irrelevant to its overall functioning will inevitably produce differences in long term behaviour compared to the original organic body. The feel of my original flesh is like the warm crackle on a vinyl record, a seemingly unquantifiable uniqueness that somehow guarantees the authenticity of the experience.

I’m unsurprisingly unsympathetic to such investment in somatic authenticity. If nothing else, these myriad differences lurking beneath the functional level are always smaller than functional differences that supposedly make no difference: if I can have my arm blown off, my liver transplanted, or even suffer significant brain damage without a consequent discontinuity of identity then borderline infinitesimal changes in my material substrate aren’t going to make any significant difference, no matter how one plays up their absolute singularity or holistic character. There’s a vast range of things that can happen to me which will drastically change my long term behaviour more than the statistical patina that functional structure abstracts away from. Furthermore, Deleuzeans should know better than to use his metaphysics to defend any claim to identity over time, as if it could be more than the effect of some transcendental illusion disguising traces of an underlying dynamic of repetition.

There remains a third, much weaker position that’s still on the table, but I don’t think it’s very satisfying. It’s what we might call the criterion of minimal spatio-temporal continuity. It’s always possible to maintain that there can be no identity over time unless there’s some spatio-temporal overlap that proceeds by sharing of components that are themselves identical over time. An infinite regress threatens here (i.e., components of components of components of…), but it’s not an intolerable one. Anyone this committed to preserving their intuitions about the necessity of material continuity will happily accept this notion as an explanatory primitive. Another way of framing this principle is to say that identity between distinct times requires identity over the intervening times. No instantaneous teleportation or mind-uploading is allowed, because it would create an unacceptable discontinuity. Nevertheless, there are still plenty of weird edge cases that will violate the intuitions they want to preserve, including fissions and fusions of every imaginable shape.

The major upshot of this position is that it permits a more elaborate ranking of candidates for identity by the extent of material continuity. The clone fortunate enough to retain a single extra cell from my original body gets to lay claim to the title, like an eldest son born seconds before his twin (or n-plets). This should be cold comfort to our material primacists (or is it ‘material supremacists’?). It’s more of a procedural hack designed to make the social bureaucracy of tracking who’s who run more smoothly than a principled decision about the nature of personal identity. A necessary but minor choice made in the assignment of variables (x1, x2, x3… xn).

4. Abased Spirits

Wait a minute… are we talking about the identity of minds or the identity of selves? When exactly did we return to the topic of personal identity? We started with questions about whether parts of the body are parts of the self, which lead us to questions about the persistence of the body and its parts over time, from which, by a process of functional abstraction, we eventually arrived at questions about the persistence of the mind over time. But somehow, in the process of rebutting objections to such cybernetic functionalism, we slipped from the language of ‘minds’ back into the language of ‘selves’, as if there were no real distinction between the two. The question is, are they really the same thing? Could there be minds without selves, or selves without minds? Could there be minds with multiple selves, or selves with multiple minds? What are the parameters of the relation between minds and selves, if they aren’t simply identical?

Of course, this terminological slippage was deliberate. But the rhetorical questions it invoked make a serious point about the ways in which certain debates collapse into one another when one hasn’t discerned the underlying motivations of one’s intellectual opponents. All the points about the mereology of minds in the last section are sound, but the objections they anticipate aren’t really coming from opponents who care about the identity conditions of minds independently of the identity conditions of selves; they come from opponents who care about the identity conditions of minds only insofar as they determine the identity conditions of selves.

Our material primacists don’t care about whether or not a cybernetically enhanced/computationally simulated brain might house the same mind, but only whether or not someone who has undergone the relevant procedure is still the same person, and they usually only care about this because they have strong introspective intuitions about the continuity of consciousness. They’re generally not worried about any discontinuities produced by natural sleep, or even those induced by general anaesthesia, but they’re terrified either of going under the cybernetician’s knife or undergoing a destructive brain upload, because they fear that whatever regains consciousness on the other side will not be them. This leaves us with yet another term to distinguish: Is a consciousness the same thing as a brain, mind, or self, or is it something else all together? What if our introspective intuitions about ‘consciousness’ are a confused and largely unhelpful addition to these debates?

At this point it’s worth restating some of my own worries about philosophical debates on the topic of personal identity. These debates take various forms, but more often than not they divide the issue in two: first, there are metaphysical questions about what kind of thing a person is, and under what conditions they persist across change, and second, there are normative questions about whether or not a person’s rights and responsibilities persist across such changes. Moreover, the normative questions are seen as essentially downstream from the metaphysical ones: work out what kind of thing a person is (e.g., whether they must exhibit continuity of memory) and this will give you the resources to answer the relevant questions about rights and responsibilities (e.g., whether someone with permanent retrograde amnesia can be held responsible for acts they can’t remember committing). My view is that this way of framing the issues hypostasises selfhood in manner that disconnects it from the normative questions which properly define it, and in so doing forces us to fall back on vague intuitions about things like continuity of consciousness, before returning to the normative questions with theories reverse engineered to meet these intuitions.

This isn’t to say that such theories can’t produce counter-intuitive conclusions, only that more often than not these are trade-offs between intuitive priorities forced by the conceptual constraints they’re operating under. For instance, there’s a possible trade-off between continuity and uniqueness. On the one hand, one can make minimal material continuity more satisfying if one abandons uniqueness: this means that multiple persons can be continuous with a past person, perhaps through some process analogous to asexual reproduction. None of the resulting clones is strictly more identical with the original than the rest, even if they might be more similar in certain respects. This makes continuity with our past selves less a matter of identity than one of descent. On the other hand, one can make the appeal to heterogeneous matter more satisfying if one abandons continuity: this makes each person a Heraclitean river, changing from moment to moment, but whose contingent enmeshment in their environment makes them absolutely singular. No attempted copy can ever be the same, no matter how similar. This makes difference from one another less a matter of quality than one of context. One can even recombine these positions on the fly, as some Deleuzo-Guattarians are wont to do, by insisting that we are a veritable swarm of selves: there’s a thread of continuity whenever we want one, but no way to isolate and copy it whenever we don’t. We can all have our cake and eat it too, insofar as, given that we contain multitudes, the one having the cake is never the one doing the eating.

It’s important to see that, in each of these cases, implicit motivations have been laundered into explicit metaphysics. This desire for a metaphysical guarantor of the intuitive features of selfhood is precisely what motivated our ancestors to postulate the soul, even if this resulted in a variety of models of its composition beyond the simple, singular, indestructible version on which the Christian tradition ultimately settled. Indeed, what’s really interesting about these more complex models is that they’re more obviously folk-psychologies, in which the different component parts of the mind are intended to explain different aspects of human behaviour. This means that there can be separate parts of the mind associated with outward bodily behaviour (e.g., reflexes and urges) and inward mental behaviour (e.g., contemplation and volition). This seems to be precisely what happens in the Chinese tradition, where the po soul articulates the passive aspect of the relationship between mind and body (yin), while the hun soul articulates the active aspect (yang). When the question of immortality gets posed within this framework, it’s subordinated to these explanatory concerns. It’s not exactly surprising that the contemplative hun is then deemed able to persist and migrate after bodily death, leaving the po behind, if only because the same idea emerges in the Platonic tradition, and ultimately feeds into Christian theology.

We can now see a more general tension at work in the evolution of theories of mind, be they folk psychological, theological, or more thoroughly philosophical: a conflict between the need to functionally decompose the mind into its component subsystems in order to explain our behaviour, and a need to impose limits on this process of decomposition in order to preserve our intuitions about our persistence as unique persons over time. As such, there must always be some primitive, indivisible part of the mind that guarantees unique persistence — some inexorably tangled knot of selfhood — but the more psychological machinery one pulls out of it in one’s quest for psychological explanation the less one can claim belongs to its ravelled essence. To put this in different terms, there’s a trade-off between psychological explicability and quintessential personality. The more one wishes merely to be who one is, the more must be locked in the black box marked ‘self’; and it doesn’t matter whether one writes ‘self’ instead of ‘immortal soul’, because mortality is a secondary issue. This means that the attempt to accuse transhumanists and fellow travellers of a crypto-theological belief in an immortal soul, while not entirely off the mark, often disguises its own theological impulses. The rush to metaphysics, materialist or otherwise, is not so much a way of exploring the problems of personal identity as it is a means for making those problems go away.

So, what get’s lost when we hypostatise selfhood in this fashion? Well… this returns us to those questions about the relations between minds and selves with which this section opened, and the even more general questions about their relations to bodies with which we are concerned. My suspicion is that, in bypassing the requisite functional abstractions, the slippage between ‘mind’ and ‘self’ has ignored the concrete possibility of alternatives to the types of bodies, minds, and selves with which we are familiar, and perhaps even rendered the matter they’re composed from into some homogeneous metaphysical soulstuff — a brute material guarantee of those introspective intuitions to which many are so attached. That these views often go hand in hand with some form of vitalism/panpsychism is thus not entirely surprising. It’s simply a further elaboration of the metaphysical limit implicit in the desire to preserve an intuitive connection between personal uniqueness and continuity of organism/consciousness. The rising popularity of animism in certain circles, the justification for which is often little more than a lazy association made with some supposedly generic subaltern (or ‘indigenous‘) worldview, demonstrates the perennial appeal of such metaphysical self-deception. In essence, the commitment to material primacy is often a disguise worn by latter day spiritualists less invested in the persistence of spirit beyond death than in its saturation of the material world.

5. Aberrant Minds

So, let’s return to the concrete possibilities: Could there be one mind with multiple selves sharing cognitive subsystems? Prima facie, this would seem to be what’s going on in cases of dissociative identity disorder. Two or more distinct personalities that share a certain base set of cognitive capacities, but with episodic memories, personality traits, and sometimes wider skillsets that diverge after some initial (often traumatic) schism. However, its status as a pathology invites interpretations that position it as a sort of delusion: one person under the mistaken impression that they are two, or even more. It doesn’t matter how elaborate this delusion is, how extensive the information partitioned between personalities, or how radical the divergences between their behaviour; it can still be presented as a dysfunctional self, rather than several functional ones. Nevertheless, there is an alternative to this pathological model: there are persons, or systems of persons, who identify as several distinct selves consensually sharing a single body. These persons represent a small and less well known segment of the neurodiversity movement that grew out of people diagnosed with autism resisting its pathologisation. Over the past few decades the internet has facilitated the growth of a thriving online ecosystem of self-identifying neurodiverse individuals with a continually evolving taxonomy of phenotypic variations; borrowing terms, ideas, and strategies from more established minority communities in the fight for recognition and accommodation. What are we to make of these contrasting attitudes?

It’s no secret that I’m a big supporter of the neurodiversity movement. I have a lot of friends out on different fringes of the neurological map, from ‘high functioning’ autism, through late life ADHD diagnoses, to schizophrenia, schizo-affective, borderline personality, aphantasia and yes, even plurality. Some of these friends consider themselves to be neurodiverse, and some of them consider themselves to have mental health problems. Not all, but most of them, would put themselves into both categories, and would not consider their mental health problems to be entirely separable from their neurodivergence. And what about me? Does my capacity to temporarily overclock my cognitive abilities at the expense of affective dysregulation, executive disinhibition, and subsequent cognitive crashes qualify as neurodivergence, mental illness, or both? Does this not further bias my attempt to adjudicate the border between pathological dissociation and divergent plurality? I have extensive and somewhat complicated views on these topics, but this post is already long enough without expanding its scope any further.

For now, I propose a methodological compromise. Let’s consider the opposing extremes in the range of positions that can be taken on the reality of plurality (also termed multiplicity). At one extreme, one can maintain that no matter how seemingly functional or insistently identifying a system is, there is strictly speaking only one person at issue. At the other, one can maintain that no matter how seemingly dysfunctional or inconsistently identifying a system is, there are precisely as many persons at issue as they present themselves as being. It should be no surprise that this opposition parallels the extremes adopted in those debates about the validity of trans identity that we touched on on earlier, and I suspect people’s opinions on the one will correlate with their opinions on the other. However, I think that we’re now touching on something deeper, insofar as we’re not simply addressing the connection between the type of person one is and the type of person one claims to be, regardless of what we think about such types (e.g., sex, gender, race, class, etc.). One can’t treat systems as a type of person without thereby deciding the question against them. They aren’t a type of person, they’re a type of mind distinguished by the fact that it contains multiple persons (of potentially differing types!).

Given this framing, my aim is to rule out the first extreme without endorsing the second. This is to insist that there are true multiples in three distinct senses: i) that it’s true that some minds contain multiple selves, ii) that we can be mistaken about which minds contain multiple selves, and iii) that this might entail the existence of uncomfortable boundary cases in which there’s a conflict between the way a mind is sincerely presented (as containing multiple distinct selves) and the way it really is (not fully multiple). This last point is the most tricky, because it risks invalidating the (multiple) identities of self-identifying systems. This is where the rhetorical parallel with debates about trans identity is unavoidable, even if we recognise that the logical parallel is less strict.

Nevertheless, no matter how tricky they are, it’s important not to avoid these issues by adopting the second extreme, for to do so is to reduce the relevant truths to more or less meaningless trivialities. It’s precisely this mistake which gets rhetorically exploited by concern trolling ‘gender critical’ feminists when they frame their position as a form of gender abolitionism. In essence, they claim that persons should be allowed to identify as whatever they wish, but only on the condition that the terms used to articulate these identities (i.e., ‘man’ and ‘woman’) have been emptied of any meaning that might have practical ramifications, which, in the limit, is all meaning — the complete abolition of gender is always kept conveniently just beyond the horizon of present political concern, while the practical work of deconstructing it is (temporarily) indexed to the traditional meaning of terms it will (eventually) abolish.

In order to defend against this rhetorical strategy, and to secure the meaningfulness of claims that enunciate parameters of selfhood, we must insist on the logical point that such claims can be made in error. This has deeper consequences for the pragmatics, epistemology, and semantics of these claims, which I’ll return to. But for now, my methodological compromise is to avoid the boundary cases where such errors must be adjudicated as much as is possible. Even so, plurality confronts us with real questions about the relationship between minds and selves that can only be addressed by abandoning our metaphysical biases and considering what can and can’t work in principle, i.e., by articulating these relationships in functional terms. What’s so significant about plurality is precisely that it really does seem to work in many cases, even though we haven’t yet figured out what it means for some configuration of minds, bodies, and selves to ‘work’ in the first place.

Of course, one could always respond that the very distinction between working and non-working mental configurations is illicit. This is a very popular position in circles that draw inspiration from ‘post-structuralism‘, which in practice usually means some mash-up of Foucault, Deleuze & Guattari, and maybe even Lacan, amongst others, filtered through a frame articulated by Derrida. The results can be more or less nuanced, but they often involve aligning and combining a range of simple symbolic oppositions (e.g., speech/writing, mind/body, male/female, human/animal, etc.) into a single overarching ‘dualist’ worldview that privileges one side over the other (what we might call ‘deconstruction by numbers’), while assimilating a variety of complex normative distinctions (e.g., normal/pathological, sane/mad, legal/criminal, straight/queer, etc.) to the same model in such a way that the imperative to reject dualism calls into question the very possibility of making valid normative distinctions (we might call this ‘transgressive genealogy’). The paradoxical character of this blanket normative judgement about normative judgements (i.e., some variant of ‘norms are bad’) is not just acceptable, but sometimes even attractive in these circles, insofar as it motivates an immanent ethics of transgression, in which each substantive value is overridden by a formal imperative to subvert every norm.

This might seem like a hasty caricature, but I’ve encountered this view in person time and time again, though the references vary from exponent to exponent. It’s a perennial fixture of art circles, precisely insofar as it generalises the immanent aesthetics of transgression that remains when one subtracts any specific commitments to compositional mediums, guiding concepts, or practical projects from the historical trajectory of contemporary art. I have a particularly vivid memory of trying to defend the seemingly innocuous proposition that we might need distinctions between good/bad, true/false, and just/unjust simply to practically orient ourselves against a hostile room full of artists and theorists during a private seminar several years ago. Still, I don’t want to paint this position a self-evidently ludicrous, even if I do think it’s pernicious. It’s important to see that its appeal lies in an abstract demand for radical autonomy, which can only be concretely expressed in acts of performative transgression: true Art consists in nothing but violating the limits implicit in every extant aesthetic configuration; and true Ethics consists in nothing but refusing every externally imposed constraint. These ritualised invocations of negative freedom are in some ways the purest expression of the residual ideals of the liberal political order. However, there’s another sense in which they reject this order, in principle, if not in practice.

As I’ve explained elsewhere, the essence of liberalism is a demand for freedom that refuses to articulate what freedom is. It may be secular in the sense that it’s agnostic about whether or not our capacity to choose for ourselves is a gift of divine provenance, but it remains thoroughly gnostic about the nature of this capacity and its enabling conditions. Liberalism remains bound by those implicit introspective intuitions about the nature of personal identity which we’ve been exploring, but it codifies them in legal systems and jurisprudential frameworks rather than transposing them into metaphysics (though economics has historically acted as a bridge between the two). It’s in the hastily patched edge cases where one sees the liberal conception of personhood begin to fray: in the way it conceives children whose autonomy is still in development, in the way it treats the elderly whose autonomy is now in decline, and in the messy patchwork of measures designed to manage those instances of neurological divergence and dysfunction with which we’re concerned. If one wants to understand the reason that every liberal violation of liberal principles has been framed in the language of paternalism, one simply needs to note that the relation between parent and child is the only model it inherited for dealing with freedom as a conditioned, created, and cultivated object; a model that is neither absolutely immutable nor even relatively fixed during the relevant historical period.

By contrast, the ‘radicalness’ of these poststructuralist tendencies consists in their willingness to push the demand for autonomy beyond the limits of these liberal frameworks, and indeed, any such framework. There’s no single way of working out what this entails. There’s a range of options to choose from, running from those essentially indistinguishable from liberalism, through those articulating types of minoritarian praxis, to those suggesting full blown alternatives to liberalism. However, this detour into political philosophy is long enough already. What we’re really interested in are the ways in which they transform the liberal subject (or soul), which are all to some extent ways of destabilising, fragmenting, or otherwise calling it into question. To be more precise, when they are confronted with the edge cases that liberalism attempts to legislate in a manner consistent with its ‘common sense’ intuitions about personhood, their response is to treat such legislation as in principle illegitimate and to subtract the contested features from the underlying common sense. They whittle away every supposedly essential element of selfhood (e.g., sex, sexuality, rationality, etc.), and compensate by multiplying the ‘positions’ that this streamlined subject can occupy (e.g., gender, orientation, discursive situation, etc.). If the liberal subject is the culmination of the characteristically modern concern with the personal autonomy that began with Renaissance humanism, then this streamlined subject might properly be called postmodern.

The problem with this (postmodern) position is that it leaves no distinction between conditions of identity and co-ordinates of identification. While liberalism struggles to get any purchase on the functional prerequisites of personhood distinct from its image of normality (e.g., to distinguish rationality from neurotypicality), its radical successors insist that every posited prerequisite is nothing but prejudice against abnormality (i.e., that rationality is an ideal on par with toxic beauty standards). The concept of agency is emptied of all content in the name of autonomy: any attempt to articulate the essence of freedom is itself interpreted as a gesture of oppression, not least because the very notion of essence has been deemed irredeemably corrupt. This is to say that the gnosticism implicit in the liberal soul has gradually made itself explicit, as its inherent nothingness is slowly revealed, and we are driven closer and closer to an apophatic conception of self-understanding. Though not necessarily metaphysical, this is eminently compatible with the weirder materialist currents discussed in the previous section. The latter provide a theoretical justification for apophasis, which is an essentially practical orientation. As such, it doesn’t much matter which flavour of materialism is chosen, insofar as the resulting mysticism cares less about the location of the spiritual than its (essential) ineffability.

What of plurality then? Well, the radical/postmodern/apophatic tendency pushes towards the second extreme. Of course, it admits that our self-understanding might be wrong, and thus that enunciations of identity/identification (e.g., “I’m the same person I was when I married you.”/”But I’m (now) a woman.”) might err — perhaps even must err — but it removes any possible basis for articulating and addressing such errors beyond further enunciations (e.g., “I was wrong, I’m not the same person anymore.”). It avoids treating plurality as a variant type of selfhood only insofar as it subtracts unity from selfhood as such. We cannot speak of the self as either one or many, but only as both not-many and not-one. This avoids disenfranchising the multiple by recognising and even valorising the ways in which we’re all already fragmented. Yet this threatens to do what we cautioned against earlier, namely, render claims about ‘plurality’ effectively meaningless. Imagine the following exchange taking place at a party, between an enthusiastic grad student who’s read a lot of D&G and a system of persons who couldn’t care less about such things:

A: “You’re multiple, that’s so cool! Everything’s a swarm… a flux… a shifting pattern of contextual relations. Down with substances, dualisms, hierarchies, norms… and all that shit! I’m a swarm too!”

B1: “We’re not a swarm, thankyouverymuch. We’re a well defined and quite stable quartet. I’ll have you know it takes some concerted effort to make this arrangement work.”

B2: “Yeah! It’s not all taking psychedelics and staying up till four in the morning talking about potatoes or whatever. Get a life, or several, you fucking tourist!”

B3: “Go easy on him 2, he’s obviously got enough problems as it is…”

B4: “Not gonna disagree with you 3, but…. Listen, A? You do you. If you want to be a swarm, go nuts. Just remember that we’re talking about real lives here, and real choices, not some abstract template you can apply to everyone regardless of how they live or what choices they make.”

No doubt some readers will be thinking that I’ve just used imaginary lives to justify my own abstract template, but bear with me here. What’s the obvious apophatic reaction to this exchange?

I think it would probably be to diffuse this disagreement by making the meaning of ‘plurality’ plural — allowing for multiple models of multiple-ness (swarming, non-swarming, and maybe more…) that can coexist without conflict. Each party is allowed to be equally right, precisely insofar as each is always slightly wrong. They are neither one nor many, but their non-unity may be further differentiated (‘swarm’/’non-swarm’) by a never-ending sequence of negations that points in the direction of some deeper meaning without ever enclosing it. But this does exactly what is being complained about, namely, impose an abstract template that ignores the concrete question at issue: Not simply, is there some vague, protean many-ness here? But rather, are there definitely many persons contained in this mind, or cohabiting in this body?

The (essential) vagueness of apophasis creates a fundamental asymmetry between the casual swarm and the dedicated system that can never resolve into the desired equality. If we validate the (precise) content of the system’s multiple-identities, then we retain a distinction between a single person identifying as (vaguely) many (which is ultimately a type of person), and several persons identifying as distinct from one another. Yet if we reject the idea that identifying is something done by (unified) persons, in order to insist that the swarm and the system are doing the same thing, then we invalidate the (disparate) content of the system’s professed identity. Even if we acknowledge that there are many different ways of being multiple, and even interstitial states that a mind passes through on its way from one to many selves, there’s still no way to resolve this asymmetry. A swarm might be an incipient system, in passage from one to many, much as an infant is an incipient person, in passage from zero to one (or more). None of this makes any difference to the precision of these numerical distinctions once distinctness has been achieved. The question of when such passage is complete might be irreducibly vague, but the question of what has thereby been completed needn’t be. Compare with some more familiar sorites cases: When does a fetus become a child? When does a child become an adult? When does a collection of cells become a person?

Of course, I may be reading too much into the poststructuralist positions I’m considering by insisting that they are strictly apophatic. However, there’s a more general way of stating my objection that rests on what I’ve quite deliberately called their postmodern character, which is to say, the manner in which they attempt to radicalise liberalism by projecting its demand for personal autonomy beyond the reach of every possible liberal order. The point is this. One cannot defend personal autonomy by dissolving the notion of personhood. This is what it means to reject the claim that any definition of autonomous agency is inherently oppressive — the concept of person has an insolubly normative core. We can’t unmoor metaphysical speculation about personal identity from normative considerations regarding transmission of rights and responsibilities between candidate persons, because it’s the need to maintain these lines of transmission that gives us our basic functional purchase on the concept of personhood. The casual swarm may contain unstructured fragments of personality, but the dedicated system sustains structured loci of integration — it incorporates a process that does the essential work of keeping track of who is responsible for what.

There’s a fairly short argument for this idea, though it depends on the principle of ought-implies-can, which I’ve defended elsewhere. If every responsibility implies a corresponding capacity, such that one cannot be held responsible if one is not capable of carrying out the responsibility, then there is some minimal set of capacities underlying every responsibility, namely, those that enable us to keep track of what we are responsible for, and to fulfil these responsibilities when their occasions arise. It doesn’t matter if the mechanisms underpinning these capacities are cognitive subsystems shared by multiple selves within the same mind. It doesn’t even matter whether these cognitive subsystems are properly unconscious, or whether they involve some conscious effort on behalf of the selves in question. All that matters is that they enable the contributions of these selves to be reliably differentiated from one another. There are two questions that naturally follow from this.

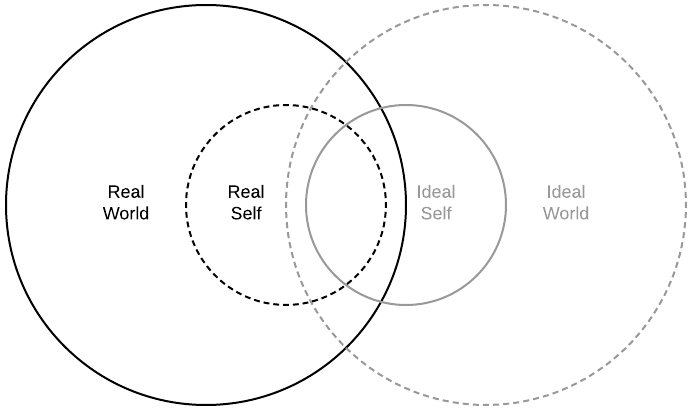

Firstly, what other capacities are implied by these basic ones? The ability to keep track of our responsibilities entails a capacity not simply to maintain an integrated representation of the world as it is, but also of the world as it should be. This differential between the real and the ideal is the force that moves us to action. It doesn’t matter whether we’re talking about simple sensorimotor expectations (e.g., the bitter tang of coffee) trickling down hierarchies of control systems (e.g., the regions of the motor cortex controlling the various muscle groups in my arm) until our perceptual input matches its reference signal (e.g., I’ve put the cup to my lips and taken a sip), combinations of persistent drives and transient affects (e.g., hunger and anxiety) emitting and modulating the relative intensities of these impulses (e.g., ratcheting thirst for caffeine but suppressing appetite), or complex practical commitments (e.g., democratic socialism and parenthood) demanding iterative elaboration of their causal consequences (e.g., canvassing, party meetings, economic policy) and navigation of their mutual incompatibilities (e.g., spending time with one’s children, sending them to private school); it doesn’t even matter how well these layers of motivational abstraction are integrated into a smooth picture of what we should do, or whether this involves flattening them into fungible quantities of subjective utility; they are united in bridging the gap between recognising the real (truth-taking) and realising the ideal (truth-making).

Secondly, how reliable must these capacities be in translating avowed commitments into successful actions? There are no doubt a wide variety of concrete dysfunctions in the above mentioned mechanisms that can result in a failure to realise ideals implicit in the responsibilities one acknowledges, but we can divide them into three basic types: failures of ability, failures of understanding, and failures of volition. In the first case, our actions are obstructed by some brute failure of the mechanisms that let us achieve certain goals, such as we might ascribe to inherent talent (e.g., physical dexterity) or acquired skill (e.g., playing the piano). In the second, they are obstructed by an incorrect, inconsistent, or merely incomplete grasp of the consequences of our commitments, which invalidates our plans for achieving them (e.g., not understanding that ‘doing the washing’ entails separating colours from whites beforehand, and so ruining them). In the third, they are obstructed by a weakness of the will, or a disconnect between an adequate grasp of our responsibility (e.g., knowing one should practice piano/do the washing) and the mechanisms that translate this into the impulses driving our behaviour (e.g., being unable to drag oneself away from the TV).

The question is, how much of each type of failure can be permitted before it invalidates one’s ability to be treated as responsible in the relevant ways? It seems that we’ve stumbled into a nest of sorites problems. However, insofar as we’re not here to adjudicate the details of specific commitments (e.g., practicing piano/doing the washing), but trying to talk about commitment in general, we can narrow the scope of this question quite considerably. Specific commitments are more often matters of practice than matters of principle, to be left to experts in the relevant domains (e.g., music/laundry) rather than philosophers unfamiliar with them. So, though we can defer questions about the reliability of mechanisms that track and fulfil specific commitments, we have to say something about the reliability of those mechanisms involved in tracking and fulfilling commitments as such. It seems uncontroversial to say that we can’t count someone who never acts upon an avowed commitment as responsible. The same might be said of anyone whose actions are at best randomly correlated with their stated intentions. Indeed, the point is that it’d be difficult to count them as ‘someone’ in the first place. These are cases of absolute dysfunction. The question is then, relatively speaking, just how unreliable do these general mechanisms have to be before they cease to support even a dysfunctional self? If we extend this to the case of plurality, it is rather, how much of these different types of failure can be attributed to dysfunctions in cognitive overlap (i.e., shared abilities/understanding) and agential differentiation (i.e., separation of distinct wills) before it no longer makes sense to talk of a dysfunctional system of selves, but only a dysfunctional mind without any persistent self?

Thankfully, as interesting as these questions are, they run up against the methodological compromise I proposed earlier. I don’t want to have to take a position on these most delicate issues, any more than I want to decide the exact moment at which a fetus becomes a potential person. I aim only to elucidate the relations between these questions, and to describe the dialectical terrain in which they’re situated. Nevertheless, one might say that these are also questions of practice, rather than principle, but that the practices in question aren’t so much those involved in training and calibrating a person’s capacities to perform specific types of task, as they are those involved in rearing and educating a person who could undertake to perform such tasks at all. This returns us to the great lacuna of liberalism: childhood. As things currently stand, there’s essentially no principle to be found here, only best practice, and there’s precious little of that as it is. This is another issue I’m going to have to put a pin in, but I’m far from the only one who thinks that childhood is a loose conceptual thread that unravels every ambient ideology if we pull on it hard enough. Far from being miraculous, the concrete genesis of freedom is the one issue that can undermine every ersatz spiritualism or emergent mysticism.

6. Alien Personae

What else is to be said about the relation between minds and selves? Asking whether one mind can have multiple selves has gotten us this far, but to go any further we must turn the question around: Can one self have multiple minds? This is a far more contentious question, because it remains stubbornly hypothetical. There’s a wealth of speculation about this possibility in science fiction and elsewhere, but no extant exemplars whose demands for recognition would force us to settle the issue. However, the question gives us new purchase on the relation between selves and bodies from which we began, insofar as a single self with multiple minds is, prima facie, a self with multiple bodies. It seems plausible that there might be minds with multiple bodies, insofar as elements of these bodies taken together might constitute a single distributed mind qua concurrent communicating system. But it’s not clear that this is the only way we can interpret cases in which there are many bodies that share a single self. Indeed, if we push this idea of a mind constituted by multiple subsystems communicating concurrently, we quickly get into situations in which it seems like these subsystems must be minds in their own right.

For example, say that I get up one morning, and realise that I have five different things I need to do today, that cannot be simultaneously achieved by a lone embodied human being. So I do what any reasonable person would do in the circumstances, and fork my consciousness into five qualitatively identical threads running in parallel on five qualitatively indistinguishable bodies. Of course, this is one of those controversial hypotheticals I mentioned above, and there’ll no doubt be many people ready to give me hell about even contemplating using terminology from computer science to articulate its parameters. Some people won’t be satisfied until literally five of me knock on their door at 2AM and start demanding they refer to me using the correct second person singular pronoun (‘Why are you here Pete?’ not ‘Why are yinz here Petes?’), or at the very least the correct plural noun (‘Why am I being accosted by a flock of Pete?’). There’ll also no doubt be some people who think I’ve just made a joke at the expense of those who insist on correct pronoun usage (‘How dare you do that Pete!), whereas I’m actually making a joke about how, if I could fork myself into five concurrent copies, I’m precisely the sort of (singular) person who would turn up at your door at 2AM and want to talk about correct pronoun usage when addressing concurrent forks (‘You seriously would do that Pete, wouldn’t you.’). Some people will never be satisfied by anything less than brute actuality. For the rest of you, read on!

Returning to the example, we might wonder what sort of concurrent interaction between these forks sustains their joint identity. Must there be some form of real time communion between brains in order for this to work (e.g., such that ‘I’ can simultaneously see out of each set of eyes)? Or is the capacity to communicate with one another in the same manner as fully separate persons sufficient:

1: “Hey Pete!”

2: “Back at you.”

1: “I’m off to re-read Kant.”

2: “I’ll tackle the washing up.”

3: “That means I’m left doing the taxes… [you are/we are/I am] such [a] bastard[s].”

One way to think about this is to consider how much information about what you’ve done in any given circumstance is necessary to make your actions consistent with what you’re doing in another circumstance. We all have memory lapses, and similar moments in which we can’t quite recall every relevant detail of something we’ve done. What’s actively available in short and medium term episodic memory, not to mention which cognitive subsystems dedicated to performing specific tasks are booted up and operating optimally, varies quite significantly over time. When I’m seriously hung over and can’t quite remember the promises I’ve made the night before, the best strategy to ensure my present actions cohere with my past ones is to ask someone else and otherwise do as little as humanly possible. As we saw in the last section, consistent behaviour over time, at least as far as one’s ongoing rights and responsibilities are concerned, is the normative substance from which selfhood is spun. What we’re doing here is moving from thinking about how one tracks the transmission of normative statuses between candidate selves that are temporally distant (phases) to thinking about how this works between candidate selves that are spatially distant (forks). The question is thus, how much communication between concurrent forks is needed to update their models of their personal rights and responsibilities, if their overall behaviour is to remain consistent?

As we said in the last section, capacities to keep track of rights and responsibilities presuppose other representational capacities, and this means that updating models of normative statuses might require updating the associated representations. If one fork has spent the afternoon opening a bank account and securing a small business loan, they can communicate the new entitlements this grants to the fork out buying supplies and the fork visiting potential premises, but they’ll probably have to include the details of the passwords or other systems of authentication by means of which these permissions can be used (i.e., so that money can be spent). Similarly, they each have to communicate to every other fork the financial commitments they’ve undertaken in order to prevent incompatibilities between the choices they’ve made in their respective situations (i.e., so that they don’t spend more money than they can afford), but they’ll also have to communicate what goods and services have thereby been purchased if they’re to ensure they purchase every item they need exactly once (i.e., so they can realise their joint enterprise).

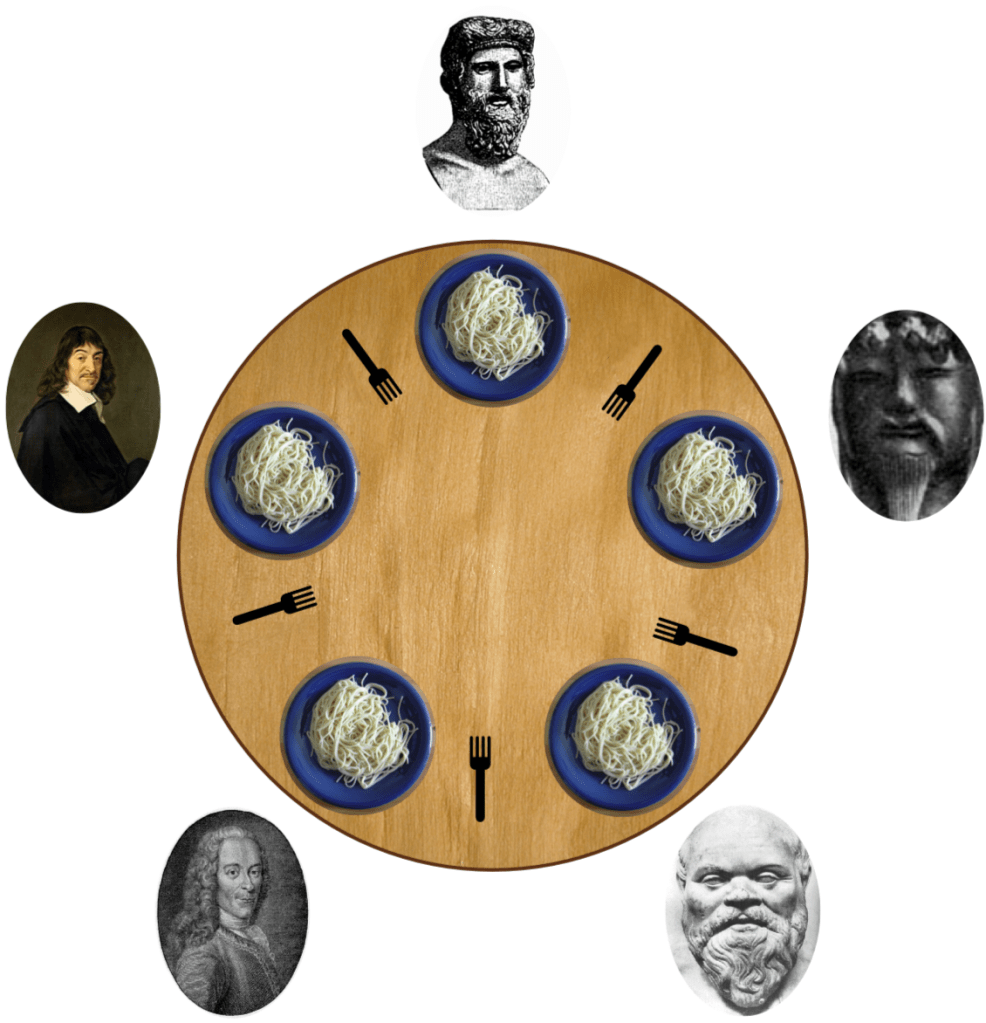

These kinds of co-ordination problems turn up even in much more intimate settings, such as when my five forks sit around a table in a restaurant trying to determine what to order, under certain constraints. Obviously, I wouldn’t order the same thing for every fork to eat (with their respective forks). I’m also the kind of person who would split myself into five forks just to try every option I’d like to eat on a restaurant menu. There are so many places I want to eat, and so little time to systematically experience everything they have to offer. But in this case, there needs to be some procedure for determining both who orders what (does each pick one at random and then break ties with rock paper scissors?), and who makes the orders and in what order they do so (do we go by some numbering, 1-5, or does 1 order for everyone?), lest their actions conflict and I end up ordering and eating nothing. It’s possible that each fork could pick the same menu item, and then turn to play rock paper scissors with the fork to their left, producing a five-fold symmetry in which it’s unclear which game resolves first. If we try to resolve them all at once we can create cycles that don’t resolve: such as when three out of five forks are tied on an option and one picks rock, one picks paper, and one picks scissors. Even worse, if the choice between rock, paper, and scissors is pseudo-random, they could all throw the same sign over and over again, even if they changed sign from turn to turn. In short, we have something of a dining philosopher’s problem on our hands.

Just in case it hasn’t sunk in fully, I’m trying to emphasise the need to talk about computational concurrency when thinking about forking. Doing so reveals problems that are forced by distribution in space, but which can sometimes turn up even when forks are in close proximity to one another. The main difference between distance and proximity is how much auxiliary information about each fork’s local environment needs to be transmitted to the others in order to make sense of the relevant normative status. Nevertheless, these problems give us some theoretical purchase on the nature of the consistency checks involved in syncing spatially distant forks that share a common self, even if questions about precisely how well these need to work in practice must be bracketed for the same reasons as those concerning temporally distant phases of the same person. One strategy for achieving such consistency, which I’ll continue to call communion, is to try and maintain something resembling a global state of the system as a whole, by creating a control centre that monitors and modulates the actions of every other element. I’ve seen people suggest that this requires some sort of quantum entanglement between brains, but that’s completely preposterous, insofar as the internal connections between cognitive subsystems within our brains need no such superfluous weirdness. In practice it just means having a primary fork (or root) acting as a control system for the rest.

However, this isn’t the only way to do things, and might generally be an undesirable way to go about them. The whole point of studying concurrent computation is to design systems composed from a collection of processes with their own local state, communicating with one another asynchronously, which are nonetheless guaranteed to behave in certain well defined ways (e.g., avoiding deadlock). It’s possible to build decentralised control systems out of such message passing (e.g., using coroutines). This means that it’s quite possible to imagine a decentralised network of concurrent communicating forks displaying unitary executive function, i.e., having a single will. Moreover, it’s possible to imagine them displaying various forms of executive dysfunction without thereby ceasing to be a single person. A singular person can easily be in two minds about a given choice, and if those two minds just happen to be in separate bodies it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re now two selves. All that’s required is some strategy for resolving such internal conflicts, and returning the overall pattern of action to something resembling consistency. Just because one of my forks takes on the role of devil’s advocate in relation to the plan of action proposed by another, doesn’t mean their interaction can’t be guaranteed to resolve in a non-catastrophic manner. Most of the arguments I usually get into with myself do.

That being said, it’s worth considering some hypothetical catastrophes: What happens if four out of five of my forks are suddenly destroyed? If they’re properly decentralised it would seem that any one of them is capable of continuing on its own. I would lose whatever memories (local state) the others had not yet synced up, but this doesn’t seem all that different from getting black out drunk and forgetting what I did last night. I’ve simply lost some versions of myself running in parallel, rather than in sequence. Nevertheless, this does raise the question of whether and how my five forks could be merged back into one. That’s a thorny problem for neurocomputational version control. I obviously can’t iron out the details here, but I think it’s fair to say that, if we recognise that a whole fork can be accidentally lost without much consequence, it’s fine for some aspects of each fork to be deliberately cut in the name of preserving others. In the limit, I might simply choose not to retain any aspect of the fork doing the washing up, as there’s nothing to be gained from such mundane experiences. The important thing to remember is that it doesn’t have to be any one fork making these editorial choices. They can be made by the system considered as a whole. Forks could bid on which bits of their connectome get priority when resolving incompatibilities, they could rely on an algorithm that makes the choice for them, or something in between. It really doesn’t matter. They’re all me.

The capacity of any one fork to survive independently seems sufficient to justify the claim that we’re dealing with multiple minds sharing a single self, but it’s worth entertaining another catastrophe: What if a fork gets isolated from the others for an extended period of time? What if it only thinks the other four have been destroyed, and so evolves independently of them for an extended period of time? What if when they finally find one another, years later, there’s too much divergence to integrate? There are really two different issues here, but differentiating them is tricky. On the one hand, the divergence between the wayward fork and the other branch might make integration technically impossible. As far as we can tell, Human memory is less about isolated episodic storage than holistic network topology, and the neurological changes generated by divergent experiences might be essentially incompatible. On the other hand, the divergence might make integration existentially undesirable. One branch or the other might object to the way in which its counterpart has evolved, in such a way that it considers itself a different person not simply in practice, but in principle.

Allow me to clarify the trickiness here. So far, I’ve argued that there can be multiple minds sharing a single self, yet precisely what makes these minds multiple is their capacity to operate independently of one another. One could object to this position that de facto independence of minds just is de jure independence of selves, and that the forks I’ve been discussing really are five distinct persons who mistakenly believe they’re identical. In this case the wayward fork has simply discovered something that was true all along. Alternatively, one could claim that the only truth of the matter regarding whether the wayward fork really is distinct is what they say about the matter. If they stipulate that they’re distinct, then they are, and that’s all there is to it. The former tries to collapse the difference between self and mind in precisely the same way as those who wish to preserve their intuitions about continuity and uniqueness, while the latter obviates questions of identity in precisely the manner that leads to the postmodern dissolution of personhood. To be clear, as in most cases, I’m generally inclined to agree with the latter position in practice, but not in principle, because it makes its case by denying that there is any matter of principle here. This puts us back in the same position we were with plurality.

Consider one more variation then: What if the wayward fork is more or less non-functional? Say it’s been badly damaged either by a sudden accident or by some gradual decline in isolation, in such a way that it simply refuses to believe that its fellows have found it. No matter what they say or do, it’s convinced that they’re imposters. It has somehow become unable to recognise them for who they are, which is to say, for who it itself is. This is similar to what happens in the Capgras delusion (in which one misrecognises others as imposters), which is itself linked to the Cotard delusion (in which one misrecognises oneself as an imposter: as already dead or otherwise unreal). In this case there’s reason to think that the main branch should be allowed to forcibly resync and/or merge with the fork, especially if this misrecognition is merely a symptom of a wider dysfunction in the capacities that enable a mind to maintain a coherent self. This is an incredibly delicate case, not least because it has parallels with the forcible re-integration of personality fragments into a unitary self, which returns us to the murky ontogenetic interval between a singular person and an organised system of selves, only without the shared body and mind. Once more, I don’t want to adjudicate specific cases, but to trace the principles governing them in outline. This means coming up with a better way of talking about candidate selves (phases/forks) and the way they (mis)recognise one another as identical or distinct, because the terms I’ve been using thus far beg the very questions we’re interested in.

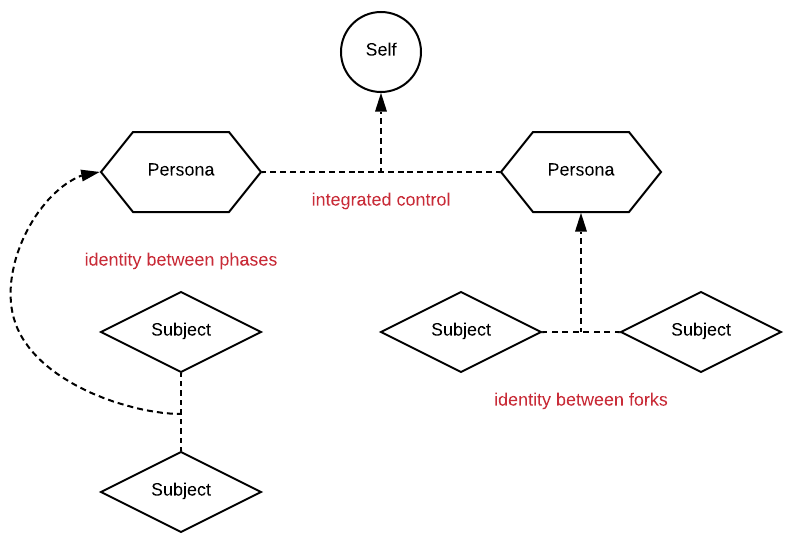

Let’s call a ‘subject’ any operative cognitive process for which there’s a meaningful question whether or not it’s ‘identical’ with another process, in the sense of belonging to the same self. Our minds contain a lot of cognitive machinery that isn’t always used at the same time, or for the same purpose. These components can be assembled on the fly into an active configuration capable of performing a task. A subject is just some such active configuration. The term is loose enough to allow recursive decomposition: subjects can contain subjects, just as tasks can contain subtasks. It applies both to processes located within the same mind-body and those that aren’t, providing a single vocabulary for describing cases of plurality (several distinct subjects in the same mind-body) and cases of forking (several identical subjects in different minds-bodies), but it can equally be used to describe more familiar forms of personhood (several identical subjects in the same mind-body). Just as we can see multiply ensouled bodies (systems) as implementing forms of collective agency internal to a single mind (i.e., explicit co-operation), we can equally see singly ensouled bodies as implementing the same sorts of individual agency as those that are multiply embodied (i.e., concurrent executive function). What might this look like?